In the five years since the first National Infrastructure Assessment, government has worked to increase the share of electricity generated by renewables, set up the UK Infrastructure Bank, devolve transport funding to major city regions, and provide industry with the direction to rapidly build gigabit capable broadband networks.

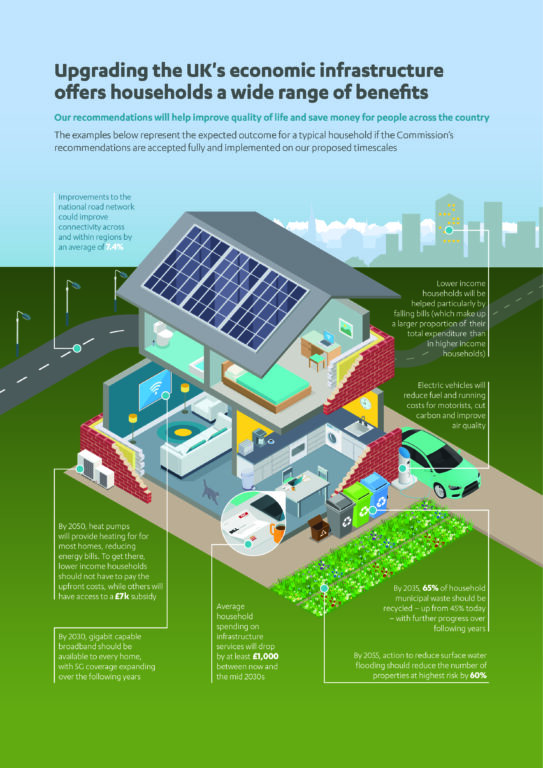

But there is more to be done to address significant deficiencies in the UK’s economic infrastructure and ensure it can meet the challenges ahead. For the first time, households face changes to reduce emissions, get off gas and oil and ensure energy security. Not only will households switch to electric vehicles, but they will need to swap their gas boilers for cleaner, more efficient heat pumps. While these technologies should roughly halve energy costs for households in the coming decades, the transition must be carefully managed to ensure the public are supported with the upfront costs and government protects the living standards of those least able to pay.

There would be significant benefits from improving connectivity. For transport networks, investment is required to facilitate sustainable trips within and between English cities. For digital networks, government should secure nationwide coverage of gigabit broadband and 5G services, and ensure the specific telecoms needs of infrastructure services are met. Increasing the quality of transport and digital networks will be necessary, although not sufficient, to reduce long standing disparities in economic outcomes and quality of life.

At the same time, all infrastructure systems should be more resilient and protect the environment. The UK’s infrastructure has proved fairly resilient over recent decades, but faces increasing exposure to shocks, including from the environment. Better maintenance and renewal of the existing asset base will be essential, as will building new infrastructure to protect households and businesses from flooding and drought.

Delivering low carbon and resilient infrastructure will require a significant increase in overall investment. The costs as well as the benefits of transforming the UK’s infrastructure will be borne by the public as taxpayers and billpayers. But making these investments will help lower costs for households and keep them lower in the longer term. These upfront investments will be paid for by consumers in their bills over the coming decades, not all at once.

While upgrading the country’s infrastructure is a major task, it is achievable, provided government makes decisions and commits to them for the long term, removes barriers to progress and supports people through the transition in a way that is both affordable and fair. This Assessment sets out recommendations to help government do so.

The core recommendations the Commission is making to government include:

- adding low carbon, flexible technologies to the electricity system to ensure supply remains reliable, and creating a new strategic energy reserve to boost Great Britain’s economic security

- taking a clear decision that electrification is the only viable option for decarbonising buildings at scale, getting the UK back on track to meet its climate targets and lowering energy bills by fully covering the costs of installing a heat pump for lower income households and offering £7,000 support to all others

- investing in public transport upgrades in England’s largest regional cities to unlock economic growth, improving underperforming parts of the national road network and developing a new comprehensive and long term rail plan which will bring productivity benefits to city regions across the North and the Midlands

- ensuring gigabit capable broadband is available nationwide by 2030 and supporting the market to roll out new 5G services

- preparing for a drier future by putting plans in place to deliver additional water supply infrastructure and reduce leakage, while also reducing water demand

- setting long term measurable targets and ensuring funded plans are in place to significantly reduce the number of properties that are at risk of flooding by 2055

- delivering a more sustainable waste system by urgently implementing reforms to meet the 65 per cent recycling target by 2035, and creating stronger incentives for investment in the recycling infrastructure that will be needed in the future.

The National Infrastructure Assessment

The Commission is required to carry out an overall assessment of the UK’s infrastructure requirements once every five years. The first Assessment was published in 2018 and has shaped many aspects of infrastructure policy, including the establishment of the UK Infrastructure Bank, increased support for renewables, committing to transition to electric vehicles, devolved budgets for local transport, deployment of gigabit capable broadband networks, and the long term direction for water resources policy.

This is the second Assessment. It covers all economic infrastructure sectors, setting out recommendations for transport, energy, water and wastewater, flood resilience, digital connectivity, and solid waste. The Assessment takes a 30 year view of the infrastructure needs within UK government competence and identifies the policies and funding to meet them.

The Assessment is guided by the Commission’s objectives to support sustainable economic growth across all regions of the UK, improve competitiveness, improve quality of life, support climate resilience and transition to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Government has given the Commission a long term funding envelope for its recommendations (the ‘fiscal remit’). Where infrastructure is financed by the private sector, and the costs of any recommendations will ultimately be met by consumers, the Commission is also required to provide a transparent assessment of the overall impact on household costs (the ‘economic remit’).

The challenges ahead

While infrastructure performs well in some areas, in others there are significant deficiencies that are holding the UK back. There has been under investment in transport systems in regional English cities, no major water resource reservoirs have been built in England in the last 30 years, too many properties are at risk of flooding, and recycling rates have not increased in a decade. This situation must improve.

Infrastructure is pivotal to addressing some of the biggest strategic challenges facing the UK, namely decarbonising the economy, boosting economic growth, and improving resilience and the environment. Proactively tackling these challenges provides an opportunity to bring major benefits to the UK. Government, regulators and industry must act urgently, with policies of sufficient scale to move the dial and enable rapid delivery on the ground. Doing so will require significant investment in economic infrastructure and the transition should be affordable and fair. This is a big task. But it is achievable. The UK has made major changes to infrastructure before — from building the electricity ‘supergrid’ in the 1950s to constructing the strategic road network in the 1960s and 70s — and can do so again.

Energy and net zero

Phasing out the use of fossil fuels to generate electricity, heat homes and power vehicles will reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and is essential for the UK to meet its legally binding climate targets. Action is now urgent with only 12 years left to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget. This shift will also bring significant economic benefits. Shocks to oil and gas prices will have a much smaller impact on the cost of living. If the UK can move fast, some businesses should be able to become leaders in new low carbon technologies. And, in the longer term, electrifying the energy system should lower energy costs for households and businesses, boosting productivity.

Supporting growth across regions

The UK must address its persistent slow economic growth and entrenched regional inequalities. Since the mid 2000s, UK productivity has fallen further behind comparator countries such as France, Germany, and the United States. In addition, the UK has long standing and self reinforcing variations in economic outcomes between and within regions. One of the reasons for this poor economic performance in recent years is low levels of investment in the UK economy compared to international peers: in the 40 years to 2019, investment in the UK averaged around 19 per cent of GDP, the lowest in the G7.

Better transport and digital networks can support economic growth in both high performing and underperforming places. Investment in transport networks can enable sustainable trips within and between cities — the main engines of economic growth. Better connections can boost productivity in cities through increasing access to high skilled labour, attracting new investment and firms, and capitalising on agglomeration benefits. Better connections between cities facilitates more efficient trade in goods and services. And delivering nationwide coverage of gigabit broadband and new 5G services can stimulate innovation and help to improve productivity in some sectors.

Improving resilience and the environment

It is important that infrastructure is both resilient to external events and protects the natural environment. Resilience shocks are infrequent and future benefits uncertain but the cost of intervention is concrete and immediate. Therefore, both the public and private sector are likely to under invest in resilience unless government acts to set expectations through service standards and ensures resilience is properly valued. Meanwhile, biodiversity is at risk and the stock of natural capital is in decline. With appropriate intervention, infrastructure can help solve, rather than exacerbate, this challenge.

This Assessment sets out recommendations to meet these strategic challenges and make the most of the opportunities they present. The Commission has used five policy principles to guide its recommendations:

- Removing barriers and accelerating decisions: Currently there are too many barriers that slow down infrastructure decision making and delivery. These make the UK a less attractive place to invest. Policy must change to facilitate faster progress.

- Taking long term decisions and demonstrating staying power: Repeatedly changing policy creates uncertainty for infrastructure operators and investors, which deters investment. It also slows the development of supply chains, driving up costs.

- Pace, not perfection: Ambitious goals must be backed up by bold policies and effective implementation. To make the rapid progress required, options must be closed down where the risk of delay is greater than the risk of making a suboptimal decision.

- Furthering devolution: Decisions made at the local level are better able to reflect local preferences, circumstances, and information. Implementation is often most effective when undertaken at the local level. As such, when done well, devolution is associated with productivity benefits and reduced regional differences. Historically, the UK has struck the wrong balance between risk sharing nationally and local autonomy on spending and taxation.

- Adaptive planning: There is inevitable uncertainty associated with long term infrastructure policy making. Decision makers must not be continually buffeted by this uncertainty, nor ignore it. In this Assessment, the Commission sets out a portfolio of policies that use adaptive pathways to effectively navigate uncertainty.

However, better policy alone is not enough to create low carbon, connected and resilient infrastructure. The Commission’s recommendations must be accompanied by effective implementation to rapidly deliver projects on the ground. This is the only way in which high quality infrastructure services — from effective, reliable and accessible transport to safe and secure energy — will be provided to people across the country, enhancing living standards for decades to come.

Energy and net zero

To tackle climate change and ensure energy security, the UK should move away from its reliance on fossil fuels. Currently around 80 per cent of the energy demand is met by fossil fuels, primarily from fossil fuel based electricity generation, natural gas boilers for heating homes and businesses, petrol and diesel cars and vans, and fossil fuels powering industry.

The solution is to replace these fossil fuels with low cost, reliable, low carbon electricity. This will require a fundamental change in the country’s energy infrastructure. Over the next 30 years the country will need:

- a larger electricity system running mostly from renewable power sources like wind and solar

- heat pumps and networks to replace gas boilers in homes and businesses

- cars and vans fuelled by clean electricity and charging infrastructure to replace petrol stations

- industry running on electricity where possible, but, where it is not, new infrastructure to supply clean hydrogen, or capture and transport the carbon emitted from burning fossil fuels to underground stores.

Moving to an electrified energy system should create cheaper, less price volatile energy in the long term. An energy system running on electricity, rather than fossil fuels, is more capital intensive and so insulated from fuel price changes. This should lower costs for households and businesses and provide more certainty over future prices. However, there will be significant upfront costs from creating the new capital assets needed and government should provide support during the transition, especially to households on lower incomes.

There have already been major steps forward. In 2022, electricity generation produced 75 per cent less emissions than it did in 1990 as renewables replaced fossil fuel powered generation. The share of new car sales that are battery electric has increased from less than one per cent in 2015 to around 16 per cent in 2022.

While there is still a long way to go in creating a secure net zero energy system, it is achievable with the right policies and a relentless focus on delivery. The UK has transformed its energy system many times before. In the 1960s and 1970s, all properties connected to the gas network were converted from town gas to natural gas in just ten years. In the 1990s ‘dash for gas’, the UK built almost 40 gas power stations, and more recently since 2010 the UK has deployed over 13 GW of offshore wind and now has the second largest offshore wind fleet in the world.

Building a secure, low carbon electricity system

By 2035, the UK needs a reliable electricity system running mostly on renewable power. Government should accelerate the deployment of offshore wind, onshore wind and solar power. These technologies should be complemented by more flexible technologies that can generate if the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing. Government should support the market to deploy electricity storage and demand side response (tools and incentives to reduce or reschedule energy usage at times of peak demand). At the same time, it’s critical that government establishes effective business models that incentivise investment in large scale hydrogen and gas with carbon capture and storage power stations that can provide electricity even during extended calm or cloudy periods. More demand for electricity means more transmission and distribution cables are required. Investment in electricity networks has not kept up with demand and therefore connections to the network are being delayed. The scale and speed of infrastructure deployment requires transformational change to planning, regulation and governance of both the transmission and distribution networks.

The electricity system will become even more important as the rest of the economy electrifies and so needs to be underpinned by a new strategic energy reserve. The energy system has proven to be vulnerable to price shocks such as that caused by Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine. Part of the reason it was so exposed was because it did not have adequate gas reserves that could be used to mitigate the impact of the shock. Government should establish a reserve of energy that can be released into the market to generate electricity in order to mitigate the effect of price shocks in the future.

Switching to electrified heat

Gas boilers, which currently heat around 88 per cent of English buildings, need to be phased out and replaced by heat pumps. Around eight million additional buildings will need to switch to low carbon heating by 2035, and all buildings by 2050. Heat pumps and heat networks are the solution. They are highly efficient, available now and being deployed rapidly in other countries. The Commission’s analysis demonstrates that there is no public policy case for hydrogen to be used to heat individual buildings. It should be ruled out as an option to enable an exclusive focus on switching to electrified heat.

Kick starting the market for heat pumps and heat networks will require urgent action and implementation from government, including a number of one off investments:

- committing £1.5 to £4.5 billion per year to improve energy efficiency and install heat pumps across the public sector estate and social housing that will help boost supply chains

- closing the gap with the lifetime cost of gas boilers by providing an initial upfront subsidy of £7,000 to households installing heat pumps or connecting to heat networks, alongside access to zero per cent financing, backed by government, for the additional cost

- committing £1 to £4 billion per year to cover the full cost of heat pump installations and support energy efficiency improvements for households on lower incomes that will be unlikely to be able to fund the costs themselves

- taking policy costs off electricity bills and ensuring the cost of running a heat pump is lower than the cost of running a gas boiler.

Effective delivery will be supported by setting devolved long term budgets for local authorities for decarbonising the homes and buildings they are responsible for. Collaboration between energy suppliers and local authorities will also ensure energy efficiency improvements are targeted at those most in need.

Rolling out electric vehicles

Increasing the adoption of electric vehicles will be key to decarbonising surface transport. Electric cars and vans are the future of road transport. As well as being zero emission, they are cheaper to run and create less air pollution.

But consumers will only purchase electric vehicles if they are confident they can charge them when they need to. Government should ensure there is a nationwide network of public charge points, reaching at least 300,000 chargers across the UK by 2030. These charge points must be spread across all regions of the country to support every consumer to make the switch.

New networks to support industry

Government has set stretching industrial decarbonisation targets. A comprehensive strategy is required to meet those targets and ensure the UK protects its industrial activity as buyers increasingly demand low carbon products. Decarbonising the industrial sector requires switching from fossil fuels to a mix of electricity, hydrogen and fossil fuels abated with carbon capture and storage. Industry needs clarity from government on which decarbonisation routes will be open to them and certainty on where supporting infrastructure will be available and by when.

Core networks of infrastructure to transmit and store hydrogen and carbon are essential by 2035. They will support industrial decarbonisation and provide the fuel needed to generate low carbon electricity. This carbon capture and storage system should have capacity to store at least 50MtCO2e per year by 2035 and the core sites should cover Grangemouth and North East Scotland, Teesside, Humberside, Merseyside, the Peak District and Southampton. Similarly, the core hydrogen transmission network should connect Grangemouth and North East Scotland, Teesside, Humberside, Merseyside and South Wales.

Supporting growth across regions

Better transport and digital networks can support economic growth across regions. Cities are the main drivers of economic growth — they have the highest employment density and largest concentrations of productive businesses. But large regional English cities are less productive than comparable European cities, partly because they have worse public transport networks. Investing in transport infrastructure can help support movement within cities and enable more efficient trade of goods and services between them, in turn helping to increase productivity. Better transport networks also improve quality of life and raise living standards, by making it easier to access public services, retail, and leisure activities. There should not be a choice between improving local and inter city transport – the UK should do both if it wants to ease constraints on growth.

Travel demand patterns have changed, to some degree, following the Covid-19 pandemic, which increased the frequency of home and hybrid working. But this has not weakened the case for long term investment. The largest cities are likely to require more capacity on their public transport networks to support economic growth over the next 20 to 30 years, and that is true even if home and hybrid working remain above pre pandemic levels.

Better digital connectivity can also boost economic growth. Improving digital connectivity can lower costs for firms, enable technological changes and innovation, and provide businesses with access to a wider pool of talent for recruitment.

In both the transport and digital sectors, there are clear actions for government to take:

- investing in the maintenance and renewal of existing transport infrastructure on both a national and local level, and planning for the effects of climate change

- enabling investment in new and improved transport networks to facilitate sustainable trips within and between cities

- delivering nationwide coverage of gigabit broadband and new 5G services to stimulate innovation and improve productivity in some sectors.

Getting cities moving

England’s largest cities have congested roads and inadequate public transport networks, which constrains their economic growth. The solution is better public transport, and more, safer, active travel. Public transport is much more space efficient than cars — a bus lane can carry around twice as many passengers per hour as a normal lane.

Government should invest £22 billion to improve public transport in the largest regional English cities to unlock economic growth. Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds and Manchester are important economic hubs within their wider regions but face the biggest transport capacity constraints. They should be the initial priorities for investment in mass transit systems. As cities will be the primary beneficiaries of better public transport, they should contribute to the costs. Cities should have the autonomy to fund as well as find local infrastructure solutions.

However, investment in public transport alone will not be sufficient to reduce congestion and improve capacity. Cities will also need to reduce car journeys into congested city centres, especially at peak times. Measures such as congestion charging and workplace parking levies can reduce car use, thereby freeing up room on the roads for more public transport. The sequencing of these transport changes will be important as reducing trips by car where there is no viable public transport alternative risks hindering, not supporting, growth and having negative social impacts.

More devolution and bigger local transport budgets are essential for better maintenance and continued transport enhancements across the country. This will give local authorities the freedom to identify local priorities, such as fixing potholes, zero emission buses and road improvements, and the resources to address them. Government should move away from centrally allocated funding pots for transport and, instead, implement flexible, long term, devolved budgets for all local authorities that are responsible for strategic transport. Government has made progress with the City Region Sustainable Transport Settlements and the recent ‘trailblazer’ deals for Greater Manchester and the West Midlands. The City Region Sustainable Transport Settlements model should now be extended beyond the Mayoral Combined Authorities, and the ‘trailblazer’ deals rolled out to all Mayoral Combined Authorities. London also requires a long term funding settlement to enhance its world class public transport network. Short term funding deals for Transport for London should be replaced with longer term capital settlements, sufficient to enable the enhancement and expansion of London’s transport services to support housing and economic growth.

Improving national road and rail networks

National road and rail networks are essential for connecting places, and so they must be well maintained. This will likely be more expensive in the future due to climate change, ageing assets and increased demand. Maintenance of existing national road and rail networks should be prioritised.

Government had developed a long term plan to improve rail performance between cities in the North and the Midlands. The High Speed 2 line between London and Manchester via Birmingham, alongside Northern Powerhouse Rail and other changes, would have significantly improved north-south and east-west rail connectivity. This investment would also have freed up capacity on the existing rail network, enabling more local and regional services to run and providing significant increases to city centre accessibility.

The second Assessment has been undertaken on the basis of the delivery of this long term rail plan. On 4th October, government announced that High Speed 2 from Birmingham to Manchester will not go ahead and set out a new package of transport schemes. This decision leaves a major gap in the UK’s rail strategy around which a number of cities have based their economic growth plans. While government has committed to reallocate the funding from cancelling the later phases of High Speed 2 to improve transport, including rail links, in the North and Midlands, it is not yet clear what the exact scope and delivery schedule is for the proposed new rail schemes. A new comprehensive, long term and fully costed plan that sets out how rail improvements will address the capacity and connectivity challenges facing city regions in the North and Midlands is needed. The Commission could support government in undertaking this work.

Alongside this, government should take forward a programme of enhancements to the road network that target underperforming sections, provide better connections between cities and facilitate trade in goods and services. It is not clear that this prioritisation happens at present – in the allocation of funding for the second Road Investment Strategy, only 22 per cent of funding allocated was in the North and the Midlands. Government should plan these enhancements on a strategic basis, aligning schemes with complementary policies that support economic growth. This should be underpinned by a national integrated strategy for interurban transport, including a pipeline of strategic improvements to the road and rail networks over the next 30 years.

Enhancing digital connectivity

Coverage of gigabit capable connectivity has improved in recent years. To ensure the UK meets the target of nationwide coverage by 2030, policy and regulation must continue to support private investment in networks and competition. Government should also finish delivering the £5 billion subsidy programme to provide coverage in the hardest to reach areas.

As the UK is still at a relatively early stage in 5G deployment, government should support a market led approach by improving the consistency of planning approvals across the country and supporting access to spectrum for localised private networks. Government should also be prepared to act fast to support deployment in uncommercial areas, should essential 5G use cases emerge. Better digital connectivity will also be vital to delivering critical functionality and strategic objectives across other infrastructure sectors. Between now and the end of 2026, government should set out plans for how the telecommunication needs of the energy, water and transport sectors will be met, including ensuring adequate access to spectrum.

Improving resilience and the environment

The UK’s infrastructure has proved fairly resilient over recent decades, but faces increasing exposure to shocks, including from the environment.

Infrastructure resilience must be taken seriously across all sectors. As the impacts of climate change increase, flood risk management infrastructure will be needed to prepare for floods, and increased water supply and water demand management will be needed to prepare for droughts.

But infrastructure systems should not just be resilient to the environment, they should also support improvements in it. Infrastructure has in the past been partly responsible for negative environmental impacts. In the future infrastructure can, instead, contribute to a healthier natural environment by, for example, increasing recycling and reducing waste, using nature based solutions for drainage and wastewater treatment and taking a strategic approach to biodiversity net gain.

Improving asset management and climate resilience

Most infrastructure assets that will be operating in 2055 have already been built. Better asset maintenance and renewal is therefore critical to achieving more resilient infrastructure. To achieve this, government should publish outcome based resilience standards for infrastructure sectors by 2025 to inform future regulatory and funding settlements. Government should also require infrastructure operators to set out the costs of meeting these standards, and work with the Met Office and standards bodies to enhance the tools available to assess this.

The UK will also need new assets to adapt to a changing climate. Currently 900,000 properties have a greater than one per cent annual risk of flooding from rivers and the sea. For surface water flooding the figure is 910,000. Government should invest in enhanced flood risk management infrastructure to reduce the risk of coastal, river and surface water flooding, with clear risk reduction targets and, in the case of surface water, improved data gathering and coordinated governance at a local level.

Without action, there will also be an over 4,000 mega litre per day gap between the demand and supply of water by 2050. Government should follow a twin track approach to drought resilience, by managing demand and increasing supply. Both reducing demand, including leakage, and providing new water infrastructure will require additional investment in the upcoming sector Price Review 2024 and beyond.

Improving the environment

Alongside improving resilience, infrastructure services should reduce their impact on the environment and leave the natural world in a better condition. This means reducing the impact of wastewater on water bodies and encouraging a more circular economy in waste disposal. Government should implement without delay its planned packaging reforms. It should also widen its restriction on plastic packaging and set individual targets, with transition funding, for local authorities, to help achieve its target recycling rate of 65 per cent by 2035. Finally, government should set stronger incentives for recycling investment and phase out the use of unabated energy from waste processing.

Government should build on its commitment to biodiversity net gain by requiring sectors with the greatest opportunity — transport, water and flood risk management — to take a strategic approach to enhancing natural capital across their estate.

Investing for the future

The Commission’s recommendations require an ambitious and sustained programme of policy change with clear direction. Realising the benefits will require a significant increase in overall investment in economic infrastructure. These investments are vital to the challenges ahead. Making them now should lead to lower overall costs for households and businesses for the long term.

The Commission’s analysis suggests that overall investment must increase from an average of around £55 billion per year over the last decade (around ten per cent of UK investment) to around £70 to 80 billion per year in the 2030s and £60 to £70 billion per year in the 2040s. Public sector investment will need to rise from £20 billion per year over the last decade to around £30 billion in the 2030s and 40s. At the latest spending review, government committed to increase this to around £30 billion for the years 2022-23 to 2024-35. This is a sharp rise, and government should ensure that it does get spent. In recent years one in every six pounds of planned capital expenditure has gone unspent. Private sector investment will need to increase from around £30 to 40 billion over the last decade to £40 to £50 billion in the 2030s and 2040s. The main areas for investment are:

- to reach net zero, around £20 to £35 billion per year between 2025 and 2050 of private sector investment in renewable generation capacity and flexible sources of generation, electricity networks, and hydrogen generation, storage and networks and a carbon capture and storage network

- to support growth across regions, investments including better public transport in cities and improved national road and rail connections, will total around £28 billion per year from the public sector — the balance of this investment will shift towards urban transport, increasing from around 40 per cent today to 50 per cent in the 2040s, reflecting the economic growth potential of cities

- to improve resilience and the environment, investments will total £1 to £1.5 billion per year from the public sector and £8 to £12 billion per year from the private sector over the next 30 years.

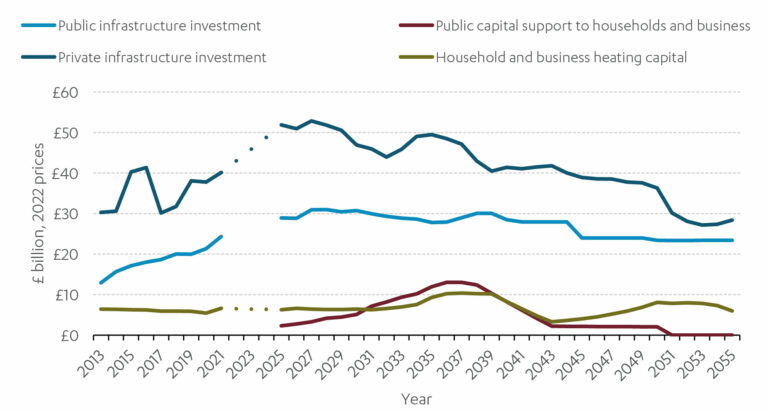

In addition, the Commission is recommending that government supports households through the energy transition to ensure it is both affordable and fair. The Commission’s recommendations involve government investing £3 to 12 billion per year to support households to decarbonise their heating systems over the next 15 years. Public support will have to be complemented by household investment of a similar size (Figure 1). Critically, these costs will not be borne up front by households as the Commission is also recommending government backed zero per cent financing is put in place so this cost is spread over time.

Figure 1: Both public and private investment will stay higher than in recent years

Public and private investment in economic infrastructure from 2013 to 2055

Source: Commission analysis.

Note: Dotted lines cover the period between latest outturn data for 2021 and the start of Commission forecasts in 2025, based on a straight line interpolation.

Note: Profile of public infrastructure investment includes the sections of HS2 that will not now go ahead

The Commission recognises the context in which it makes the case for increased investment, which is ultimately funded by households and businesses — either through taxation, bills, or the price of products purchased. Since 2019, households have faced a series of adverse shocks, most recently on cost of living. A significant proportion of the population are in fuel poverty.

But making these investments will help lower costs for households and keep them low in the longer term. These upfront investments will be paid by consumers in their bills over the coming decades, not all at once.

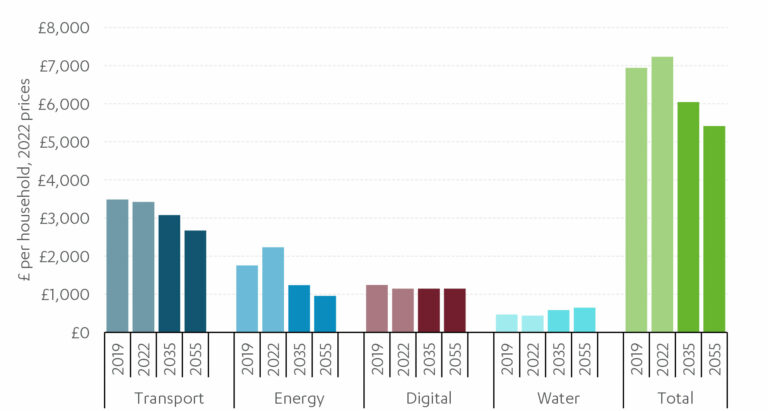

In total, overall household spending on infrastructure should fall from today’s £7,300 per household to around £5,500 to £6,600 by the mid 2030s. For the next few years, energy costs will largely be driven by the volatile and difficult to predict gas price. But beyond that, the key driver of lower household costs is transitioning away from fossil fuels and onto cheaper, reliable low carbon electricity. A fossil fuel based system has high operating costs. Natural gas, coal, or oil must be continually purchased and burned to generate electricity. A system running on renewables, heat pumps and electric cars will have high upfront costs that are paid for slowly over time but it is cheaper to run. Offshore wind, onshore wind and solar farms have low operating costs as they require no fuel inputs. Heat pumps and electric vehicles are much more efficient than gas boilers and petrol or diesel cars. The cheaper operating costs of a low carbon energy system more than offset the costs of paying for the new infrastructure, leading to lower household costs.

This reduction in energy costs should be much greater than the upward pressure on bills from increased investment required in the water sector to reduce both pollution and drought risk.

Figure 2: Overall household spending on infrastructure should fall by at least £1,000 from today’s high levels

Household spending on infrastructure 2019 to 2055

Source: Commission analysis

Critically, it is not only the average household cost impact that is important, but also the impact on lower income households. The Commission has sought to ensure its recommendations in this Assessment, if carefully implemented, will not have a disproportionate impact on such households, by undertaking distributional analysis, engaging with experts, and commissioning social research.

Making good decisions, fast

The majority of the investment needed will come from private capital. Securing this wave of private sector investment will require better policy and decision making. There is private finance available but, to secure it, the UK must be able to attract investors based on the strength of its policy and regulatory environment and the returns available from projects.

Government must be able to make good decisions, fast. There need to be changes to planning, predictable regulatory models that allow rates of return commensurate with the level of risk, better strategic policy direction from government, increased use of competition and good infrastructure design. All this can help secure private investment, although changes to public investment decisions are also essential.

An effective planning system that enables good decisions to be made swiftly is essential for attracting investment. While the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Planning framework initially worked well, it has deteriorated in recent years — consenting timelines have slowed by 65 per cent. Government has taken some positive steps towards reform, but more is needed, including: updates to National Policy Statements at least every five years, better use of environmental data, a meaningful and consistent approach to community benefits, integrated spatial planning, and more robust oversight and accountability at the centre of government.

The UK’s system of economic regulation needs to be updated to enable the transformational change required to tackle net zero and climate resilience. It is critical that regulation maintains the confidence of both the public and the private sector. To do this, regulators must ensure that the private companies they regulate are financially sustainable. This includes considering appropriate gearing ratios and linking returns to both risk and performance. Greater consistency is required across price regulated regimes, including in how the allowed cost of capital is set.

Further action is also needed to support investment, including:

- Strategic direction from government to regulators through regular Strategic Policy Statements for each sector. These statements should set out a coherent long term vision for sectors aligned with government’s policy priorities. At a time when the water and energy sectors need transformational change, not just marginal efficiency improvements, regular Strategic Policy Statements are essential for giving regulators clarity to prioritise investment, especially when it is required ahead of need.

- Enhanced use of competition, where appropriate. Investment aimed at addressing strategic challenges will be made in the context of high levels of uncertainty and rapid technological change. One way to capitalise on this opportunity for innovation is through an increased role for competition. Removing some major strategic investments from the price controls and opening them to competition will both boost innovation and give infrastructure providers confidence to deliver long term projects within a stable regulatory environment. However, competition will not be appropriate in all circumstances. In some cases, introducing competition could slow delivery in the short term or hinder the coordinated delivery of networks.

- New business models are needed to support deployment of hydrogen and carbon capture and storage networks, and new forms of flexible electricity generation. These business models must provide investors with clarity and certainty, alongside an appropriate rate of return and replicate the success of the contracts for difference model for renewable electricity generation.

Good infrastructure design provides value for people, places, and the climate while also helping projects finish on time and at lower cost. Embedding this process into the culture of delivery from the outset of projects can improve aesthetics, drive wide community engagement and maximise the benefits of the project.

Having visible and long term pipelines of investment opportunities will be necessary for the market to invest in the skills and supply chains essential to deliver the required infrastructure on time and to budget.

Effective policy and decision making are not just essential to support private sector investment, they are also critical for public sector investment too. Major infrastructure projects should be given separate budgets for their lifetime. The largest projects should be given their own ‘departmental style’ settlements with explicit contingency budgets to ensure that cost or time overruns don’t prevent other smaller projects from being taken forward. Finally, government should account for maintenance and renewals spending separately to enhancements so that it does not get deprioritised.

There is no time to lose

Delivering the Commission’s package of recommendations will ensure the UK has low carbon and resilient infrastructure for the coming decades, which can support economic growth across regions and protect the natural environment.

But the UK must act fast. This Assessment sets out the steps government should take to capitalise on the areas where the UK has already made good progress, and to catch up in those areas where it risks falling behind.

While meeting the UK’s economic infrastructure needs will incur significant, if manageable, costs, the costs of inaction would almost certainly be greater. The UK has been here before: the inadequacies of infrastructure today reflect past failures to act and invest for the long term. Policies have too often been delayed where the benefits of acting earlier would have outweighed the initial costs. Rather than repeating this mistake, government must act now to secure infrastructure that is fit for the future. Implementing the Commission’s ambitious set of recommendations will require bold decisions, long term thinking, and support for households during the transition. The transformation of the UK’s infrastructure will require determined political leadership at both national and local level. It will also demand close collaboration between government, regulators and industry.

The good news is that significant benefits can be realised for households, businesses and communities across the UK — and crucially, they can be achieved in a way that is affordable and fair.